Python as a language is comparatively simple. And I believe, that you can learn quite a lot about Python and its features, just by learning what all of its builtins are, and what they do. And to back up that claim, I'll be doing just that.

Just to be clear, this is not going to be a tutorial post. Covering such a vast amount of material in a single blog post, while starting from the beginning is pretty much impossible. So I'll be assuming you have a basic to intermediate understanding of Python. But other than that, we should be good to go.

Index

- Index

- So what's a builtin?

- ALL the builtins

- Exceptions

- Constants

- Funky globals

- All the builtins, one by one

compile,execandeval: How the code worksglobalsandlocals: Where everything is storedinputandprint: The bread and butterstr,bytes,int,bool,floatandcomplex: The five primitivesobject: The basetype: The class factoryhashandid: The equality fundamentalsdirandvars: Everything is a dictionaryhasattr,getattr,setattranddelattr: Attribute helperssuper: The power of inheritanceproperty,classmethodandstaticmethod: Method decoratorslist,tuple,dict,setandfrozenset: The containersbytearrayandmemoryview: Better byte interfacesbin,hex,oct,ord,chrandascii: Basic conversionsformat: Easy text transformsanyandallabs,divmod,powandround: Math basicsisinstanceandissubclass: Runtime type checkingcallableand duck typing basicssortedandreversed: Sequence manipulatorsmapandfilter: Functional primitiveslen,max,minandsum: Aggregate functionsiterandnext: Advanced iterationrange,enumerateandzip: Convenient iterationslicebreakpoint: built-in debuggingopen: File I/Orepr: Developer conveniencehelp,exitandquit: site builtinscopyright,credits,license: Important texts

- So what's next?

- The end

So what's a builtin?

A builtin in Python is everything that lives in the builtins module.

To understand this better, you'll need to learn about the L.E.G.B. rule.

^ This defines the order of scopes in which variables are looked up in Python. It stands for:

- Local scope

- Enclosing (or nonlocal) scope

- Global scope

- Builtin scope

Local scope

The local scope refers to the scope that comes with the current function or class you are in. Every function call and class instantiation creates a fresh local scope for you, to hold local variables in.

Here's an example:

x = 11

print(x)

def some_function():

x = 22

print(x)

some_function()

print(x)Running this code outputs:

11

22

11So here's what's happening: Doing x = 22 defines a new variable inside some_function that is in its own local namespace. After that point, whenever the function refers to x, it means the one in its own scope. Accessing x outside of some_function refers to the one defined outside.

Enclosing scope

The enclosing scope (or nonlocal scope) refers to the scope of the classes or functions inside which the current function/class lives.

... I can already see half of you going 🤨 right now. So let me explain with an example:

x = 11

def outer_function():

x = 22

y = 789

def inner_function():

x = 33

print('Inner x:', x)

print('Enclosing y:', y)

inner_function()

print('Outer x:', x)

outer_function()

print('Global x:', x)The output of this is:

Inner x: 33

Enclosing y: 789

Outer x: 22

Global x: 11What it essentially means is that every new function/class creates its own local scope, separate from its outer environment. Trying to access an outer variable will work, but any variable created in the local scope does not affect the outer scope. This is why redefining x to be 33 inside the inner function doesn't affect the outer or global definitions of x.

But what if I want to affect the outer scope?

To do that, you can use the nonlocal keyword in Python to tell the interpreter that you don't mean to define a new variable in the local scope, but you want to modify the one in the enclosing scope.

def outer_function():

x = 11

def inner_function():

nonlocal x

x = 22

print('Inner x:', x)

inner_function()

print('Outer x:', x)This prints:

Inner x: 22

Outer x: 22Global scope

Global scope (or module scope) simply refers to the scope where all the module's top-level variables, functions and classes are defined.

A "module" is any python file or package that can be run or imported. For eg. time is a module (as you can do import time in your code), and time.sleep() is a function defined in time module's global scope.

Every module in Python has a few pre-defined globals, such as __name__ and __doc__, which refer to the module's name and the module's docstring, respectively. You can try this in the REPL:

>>> print(__name__)

__main__

>>> print(__doc__)

None

>>> import time

>>> time.__name__

'time'

>>> time.__doc__

'This module provides various functions to manipulate time values.'Builtin scope

Now we get to the topic of this blog -- the builtin scope.

So there's two things to know about the builtin scope in Python:

- It's the scope where essentially all of Python's top level functions are defined, such as

len,rangeandprint. - When a variable is not found in the local, enclosing or global scope, Python looks for it in the builtins.

You can inspect the builtins directly if you want, by importing the builtins module, and checking methods inside it:

>>> import builtins

>>> builtins.a # press <Tab> here

builtins.abs( builtins.all( builtins.any( builtins.ascii(And for some reason unknown to me, Python exposes the builtins module as __builtins__ by default in the global namespace. So you can also access __builtins__ directly, without importing anything. Note, that __builtins__ being available is a CPython implementation detail, and other Python implementations might not have it. import builtins is the most correct way to access the builtins module.

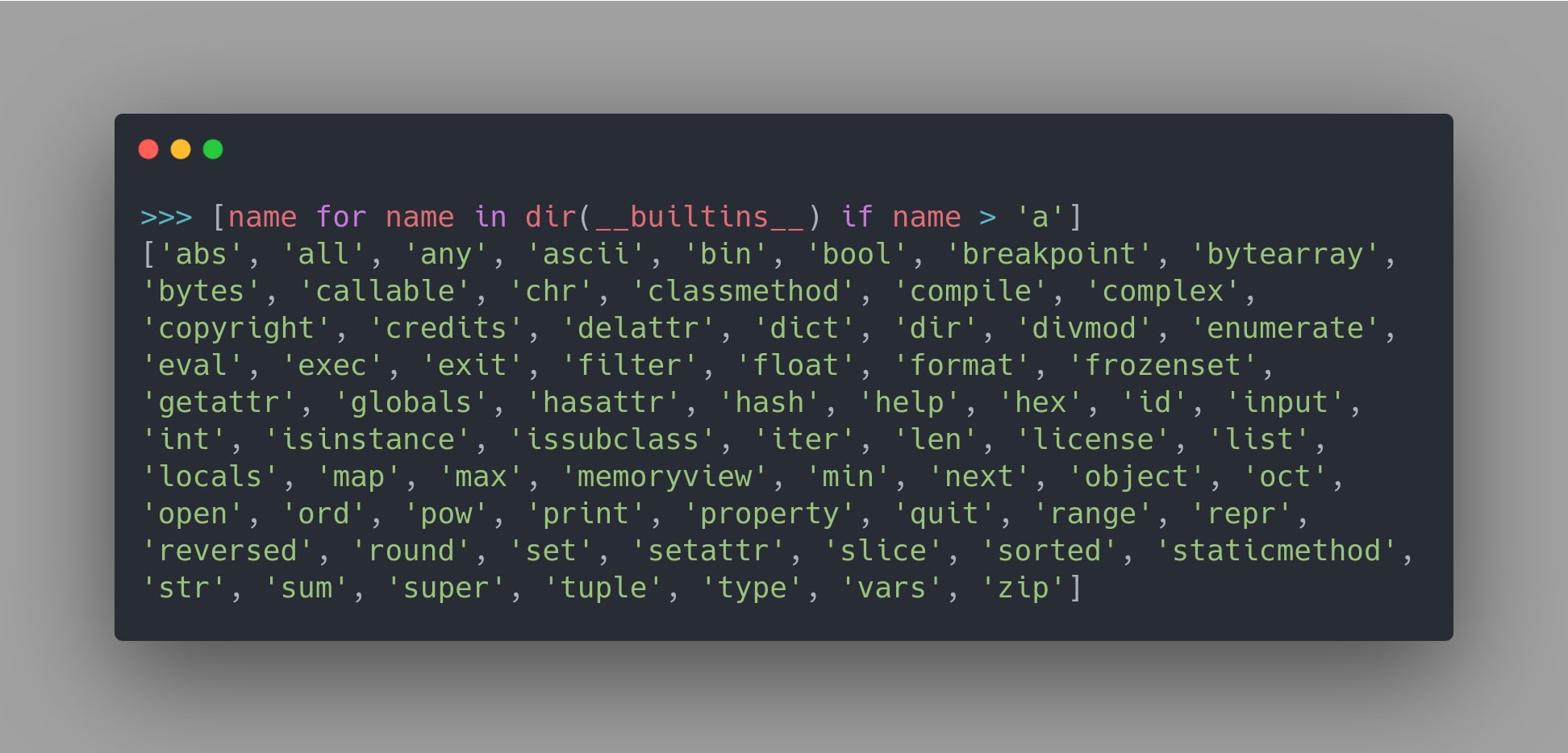

ALL the builtins

You can use the dir function to print all the variables defined inside a module or class. So let's use that to list out all of the builtins:

>>> print(dir(__builtins__))

['ArithmeticError', 'AssertionError', 'AttributeError', 'BaseException',

'BlockingIOError', 'BrokenPipeError', 'BufferError', 'BytesWarning',

'ChildProcessError', 'ConnectionAbortedError', 'ConnectionError',

'ConnectionRefusedError', 'ConnectionResetError', 'DeprecationWarning',

'EOFError', 'Ellipsis', 'EnvironmentError', 'Exception', 'False',

'FileExistsError', 'FileNotFoundError', 'FloatingPointError',

'FutureWarning', 'GeneratorExit', 'IOError', 'ImportError',

'ImportWarning', 'IndentationError', 'IndexError', 'InterruptedError',

'IsADirectoryError', 'KeyError', 'KeyboardInterrupt', 'LookupError',

'MemoryError', 'ModuleNotFoundError', 'NameError', 'None',

'NotADirectoryError', 'NotImplemented', 'NotImplementedError',

'OSError', 'OverflowError', 'PendingDeprecationWarning',

'PermissionError', 'ProcessLookupError', 'RecursionError',

'ReferenceError', 'ResourceWarning', 'RuntimeError', 'RuntimeWarning',

'StopAsyncIteration', 'StopIteration', 'SyntaxError', 'SyntaxWarning',

'SystemError', 'SystemExit', 'TabError', 'TimeoutError', 'True',

'TypeError', 'UnboundLocalError', 'UnicodeDecodeError',

'UnicodeEncodeError', 'UnicodeError', 'UnicodeTranslateError',

'UnicodeWarning', 'UserWarning', 'ValueError', 'Warning',

'ZeroDivisionError', '__build_class__', '__debug__', '__doc__',

'__import__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__',

'abs', 'all', 'any', 'ascii', 'bin', 'bool', 'breakpoint', 'bytearray',

'bytes', 'callable', 'chr', 'classmethod', 'compile', 'complex',

'copyright', 'credits', 'delattr', 'dict', 'dir', 'divmod', 'enumerate',

'eval', 'exec', 'exit', 'filter', 'float', 'format', 'frozenset',

'getattr', 'globals', 'hasattr', 'hash', 'help', 'hex', 'id', 'input',

'int', 'isinstance', 'issubclass', 'iter', 'len', 'license', 'list',

'locals', 'map', 'max', 'memoryview', 'min', 'next', 'object', 'oct',

'open', 'ord', 'pow', 'print', 'property', 'quit', 'range', 'repr',

'reversed', 'round', 'set', 'setattr', 'slice', 'sorted',

'staticmethod', 'str', 'sum', 'super', 'tuple', 'type', 'vars', 'zip']...yeah, there's a lot. But don't worry, we'll break these down into various groups, and knock them down one by one.

So let's tackle the biggest group by far:

Exceptions

Python has 66 built-in exception classes (so far), each one intended to be used by the user, the standard library and everyone else, to serve as meaningful ways to interpret and catch errors in your code.

To explain exactly why there's separate Exception classes in Python, here's a quick example:

def fetch_from_cache(key):

"""Returns a key's value from cached items."""

if key is None:

raise ValueError('key must not be None')

return cached_items[key]

def get_value(key):

try:

value = fetch_from_cache(key)

except KeyError:

value = fetch_from_api(key)

return valueFocus on the get_value function. It's supposed to return a cached value if it exists, otherwise fetch data from an API.

There's 3 things that can happen in that function:

-

If the

keyis not in the cache, trying to accesscached_items[key]raises aKeyError. This is caught in thetryblock, and an API call is made to get the data. -

If they

keyis present in the cache, it is returned as is. -

There's also a third case, where

keyisNone.If the key is

None,fetch_from_cacheraises aValueError, indicating that the value provided to this function was inappropriate. And since thetryblock only catchesKeyError, this error is shown directly to the user.>>> x = None >>> get_value(x) Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> File "<stdin>", line 3, in get_value File "<stdin>", line 3, in fetch_from_cache ValueError: key must not be None >>>

If ValueError and KeyError weren't predefined, meaningful error types, there wouldn't be any way to differentiate between error types in this way.

Extras: Exception trivia

A fun fact about exceptions is that they can be sub-classed to make your own, more specific error types. For example, you can create a InvalidEmailError extending ValueError, to raise errors when you expected to receive an E-mail string, but it wasn't valid. If you do this, you'll be able to catch InvalidEmailError by doing except ValueError as well.

Another fact about exceptions is that every exception is a subclass of BaseException, and nearly all of them are subclasses of Exception, other than a few that aren't supposed to be normally caught. So if you ever wanted to be able to catch any exception normally thrown by code, you could do

except Exception: ...and if you wanted to catch every possible error, you could do

except BaseException: ...Doing that would even catch KeyboardInterrupt, which would make you unable to close your program by pressing Ctrl+C. To read about the hierarchy of which Error is subclassed from which in Python, you can check the Exception hierarchy in the docs.

Now I should point out that not all uppercase values in that output above were exception types, there's in-fact, 1 another type of built-in objects in Python that are uppercase: constants. So let's talk about those.

Constants

There's exactly 5 constants: True, False, None, Ellipsis, and NotImplemented.

True, False and None are the most obvious constants.

Ellipsis is an interesting one, and it's actually represented in two forms: the word Ellipsis, and the symbol .... It mostly exists to support type annotations, and for some very fancy slicing support.

NotImplemented is the most interesting of them all (other than the fact that True and False actually function as 1 and 0 if you didn't know that, but I digress). NotImplemented is used inside a class' operator definitions, when you want to tell Python that a certain operator isn't defined for this class.

Now I should mention that all objects in Python can add support for all Python operators, such as +, -, +=, etc., by defining special methods inside their class, such as __add__ for +, __iadd__ for +=, and so on.

Let's see a quick example of that:

class MyNumber:

def __add__(self, other):

return other + 42This results in our object acting as the value 42 during addition:

>>> num = MyNumber()

>>> num + 3

45

>>> num + 100

142Extras: right-operators

If you're wondering from the code example above why I didn't try to do 3 + num, it's because it doesn't work yet:

>>> 100 + num

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'MyNumber'But, support for that can be added pretty easily by adding the __radd__ operator, which adds support for right-addition:

class MyNumber:

def __add__(self, other):

return other + 42

def __radd__(self, other):

return other + 42As a bonus, this also adds support for adding two MyNumber classes together:

>>> num = MyNumber()

>>> num + 100

142

>>> 3 + num

45

>>> num + num

84But let's say you only want to support integer addition with this class, and not floats. This is where you'd use NotImplemented:

class MyNumber:

def __add__(self, other):

if isinstance(other, float):

return NotImplemented

return other + 42Returning NotImplemented from an operator method tells Python that this is an unsupported operation. Python then conveniently wraps this into a TypeError with a meaningful message:

>>> n + 0.12

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'MyNumber' and 'float'

>>> n + 10

52A weird fact about constants is that they aren't even implemented in Python, they're implemented directly in C code, like this for example.

Funky globals

There's another group of odd-looking values in the builtins output we saw above: values like __spec__, __loader__, __debug__ etc.

These are actually not unique to the builtins module. These properties are all present in the global scope of every module in Python, as they are module attributes. These hold information about the module that is required for the import machinery. Let's take a look at them:

__name__

Contains the name of the module. For example, builtins.__name__ will be the string 'builtins'. When you run a Python file, that is also run as a module, and the module name for that is __main__. This should explain how if __name__ == '__main__' works when used in Python files.

__doc__

Contains the module's docstring. It's what's shown as the module description when you do help(module_name).

>>> import time

>>> print(time.__doc__)

This module provides various functions to manipulate time values.

There are two standard representations of time. One is the number...

>>> help(time)

Help on built-in module time:

NAME

time - This module provides various functions to manipulate time values.

DESCRIPTION

There are two standard representations of time. One is the number...More Python trivia: this is why the PEP8 style guide says "docstrings should have a line length of 72 characters": because docstrings can be indented upto two levels in the

help()message, so to neatly fit on an 80-character wide terminal they must be at a maximum, 72 characters wide.

__package__

The package to which this module belongs. For top-level modules it is the same as __name__. For sub-modules it is the package's __name__. For example:

>>> import urllib.request

>>> urllib.__package__

'urllib'

>>> urllib.request.__name__

'urllib.request'

>>> urllib.request.__package__

'urllib'__spec__

This refers to the module spec. It contains metadata such as the module name, what kind of module it is, as well as how it was created and loaded.

$ tree mytest

mytest

└── a

└── b.py

1 directory, 1 file

$ python -q

>>> import mytest.a.b

>>> mytest.__spec__

ModuleSpec(name='mytest', loader=<_frozen_importlib_external._NamespaceLoader object at 0x7f28c767e5e0>, submodule_search_locations=_NamespacePath(['/tmp/mytest']))

>>> mytest.a.b.__spec__

ModuleSpec(name='mytest.a.b', loader=<_frozen_importlib_external.SourceFileLoader object at 0x7f28c767e430>, origin='/tmp/mytest/a/b.py')You can see through it that, mytest was located using something called NamespaceLoader from the directory /tmp/mytest, and mytest.a.b was loaded using a SourceFileLoader, from the source file b.py.

__loader__

Let's see what this is, directly in the REPL:

>>> __loader__

<class '_frozen_importlib.BuiltinImporter'>The __loader__ is set to the loader object that the import machinery used when loading the module. This specific one is defined within the _frozen_importlib module, and is what's used to import the builtin modules.

Looking slightly more closely at the example before this, you might notice that the loader attributes of the module spec are Loader classes that come from the slightly different _frozen_importlib_external module.

So you might ask, what are these weird _frozen modules? Well, my friend, it's exactly as they say -- they're frozen modules.

The actual source code of these two modules is actually inside the importlib.machinery module. These _frozen aliases are frozen versions of the source code of these loaders. To create a frozen module, the Python code is compiled to a code object, marshalled into a file, and then added to the Python executable.

If you have no idea what that meant, don't worry, we will cover this in detail later.

Python freezes these two modules because they implement the core of the import system and, thus, cannot be imported like other Python files when the interpreter boots up. Essentially, they are needed to exist to bootstrap the import system.

Funnily enough, there's another well-defined frozen module in Python: it's __hello__:

>>> import __hello__

Hello world!Is this the shortest hello world code in any language? :P

Well this __hello__ module was originally added to Python as a test for frozen modules, to see whether or not they work properly. It has stayed in the language as an easter egg ever since.

__import__

__import__ is the builtin function that defines how import statements work in Python.

>>> import random

>>> random

<module 'random' from '/usr/lib/python3.9/random.py'>

>>> __import__('random')

<module 'random' from '/usr/lib/python3.9/random.py'>

>>> np = __import__('numpy') # Same as doing 'import numpy as np'

>>> np

<module 'numpy' from '/home/tushar/.local/lib/python3.9/site-packages/numpy/__init__.py'>Essentially, every import statement can be translated into an __import__ function call. Internally, that's pretty much what Python is doing to the import statements (but directly in C).

Now, there's three more of these properties left:

__debug__and__build_class__which are only present globally and are not module variables, and__cached__, which is only present in imported modules.

__debug__

This is a global, constant value in Python, which is almost always set to True.

What it refers to, is Python running in debug mode. And Python always runs in debug mode by default.

The other mode that Python can run in, is "optimized mode". To run python in "optimized mode", you can invoke it by passing the -O flag. And all it does, is prevents assert statements from doing anything (at least so far), which in all honesty, isn't really useful at all.

$ python

>>> __debug__

True

>>> assert False, 'some error'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AssertionError: some error

>>>

$ python -O

>>> __debug__

False

>>> assert False, 'some error'

>>> # Didn't raise any error.Also, __debug__, True, False and None are the only true constants in Python, i.e. these 4 are the only global variables in Python that you cannot overwrite with a new value.

>>> True = 42

File "<stdin>", line 1

True = 42

^

SyntaxError: cannot assign to True

>>> __debug__ = False

File "<stdin>", line 1

SyntaxError: cannot assign to __debug____build_class__

This global was added in Python 3.1, to allow for class definitions to accept arbitrary positional and keyword arguments. There are long, technical reasons to why this is a feature, and it touches advanced topics like metaclasses, so unfortunately I won't be explaining why it exists.

But all you need to know is that this is what allows you to do things like this while making a class:

>>> class C:

... def __init_subclass__(self, **kwargs):

... print(f'Subclass got data: {kwargs}')

...

>>> class D(C, num=42, data='xyz'):

... pass

...

Subclass got data: {'num': 42, 'data': 'xyz'}

>>>Before Python 3.1, The class creation syntax only allowed passing base classes to inherit from, and a metaclass property. The new requirements were to allow variable number of positional and keyword arguments. This would be a bit messy and complex to add to the language.

But, we already have this, of course, in the code for calling regular functions. So it was proposed that the Class X(...) syntax will simply delegate to a function call underneath: __build_class__('X', ...).

You can read more in PEP 3115 and in this email from Guido.

__cached__

This is an interesting one.

When you import a module, the __cached__ property stores the path of the cached file of the compiled Python bytecode of that module.

"What?!", you might be saying, "Python? Compiled?"

Yeah. Python is compiled. In fact, all Python code is compiled, but not to machine code -- to bytecode. Let me explain this point by explaining how Python runs your code.

Here are the steps that the Python interpreter takes to run your code:

- It takes your source file, and parses it into a syntax tree. The syntax tree is a representation of your code that can be more easily understood by a program. It finds and reports any errors in the code's syntax, and ensures that there are no ambiguities.

- The next step is to compile this syntax tree into bytecode. Bytecode is a set of micro-instructions for Python's virtual machine. This "virtual machine" is where Python's interpreter logic resides. It essentially emulates a very simple stack-based computer on your machine, in order to execute the Python code written by you.

- This bytecode-form of your code is then run on the Python VM. The bytecode instructions are simple things like pushing and popping data off the current stack. Each of these instructions, when run one after the other, executes the entire program.

We will take a really detailed example of the steps above, in the next section. Hang tight!

Now since the "compiling to bytecode" step above takes a noticeable amount of time when you import a module, Python stores (marshalls) the bytecode into a .pyc file, and stores it in a folder called __pycache__. The __cached__ parameter of the imported module then points to this .pyc file.

When the same module is imported again at a later time, Python checks if a .pyc version of the module exists, and then directly imports the already-compiled version instead, saving a bunch of time and computation.

If you're wondering: yes, you can directly run or import a .pyc file in Python code, just like a .py file:

>>> import test

>>> test.__cached__

'/usr/lib/python3.9/test/__pycache__/__init__.cpython-39.pyc'

>>> exit()

$ cp '/usr/lib/python3.9/test/__pycache__/__init__.cpython-39.pyc' cached_test.pyc

$ python

>>> import cached_test # Runs!

>>>All the builtins, one by one

Now we can finally get on with builtins. And, to build upon the last section, let's start this off with some of the most interesting ones, the ones that build the basis of Python as a language.

compile, exec and eval: How the code works

In the previous section, we saw the 3 steps required to run some python code. This section will get into details about the 3 steps, and how you can observe exactly what Python is doing.

Let's take this code as an example:

x = [1, 2]

print(x)You can save this code into a file and run it, or type it in the Python REPL. In both the cases, you'll get an output of [1, 2].

Or thirdly, you can give the program as a string to Python's builtin function exec:

>>> code = '''

... x = [1, 2]

... print(x)

... '''

>>> exec(code)

[1, 2]exec (short for execute) takes in some Python code as a string, and runs it as Python code. By default, exec will run in the same scope as the rest of your code, which means, that it can read and manipulate variables just like any other piece of code in your Python file.

>>> x = 5

>>> exec('print(x)')

5exec allows you to run truly dynamic code at runtime. You could, for example, download a Python file from the internet at runtime, pass its content to exec and it will run it for you. (But please, never, ever do that.)

For the most part, you don't really need exec while writing your code. It's useful for implementing some really dynamic behaviour (such as creating a dynamic class at runtime, like collections.namedtuple does), or to modify the code being read from a Python file (like in zxpy).

But, that's not the main topic of discussion today. We must learn how exec does all of these fancy runtime things.

exec can not only take in a string and run it as code, it can also take in a code object.

Code objects are the "bytecode" version of Python programs, as discussed before. They contain not only the exact instructions generated from your Python code, but it also stores things like the variables and the constants used inside that piece of code.

Code objects are generated from ASTs (abstract syntax trees), which are themselves generated by a parser that runs on a string of code.

Now, if you're still here after all that nonsense, let's try to learn this by example instead. We'll first generate an AST from our code using the ast module:

>>> import ast

>>> code = '''

... x = [1, 2]

... print(x)

... '''

>>> tree = ast.parse(code)

>>> print(ast.dump(tree, indent=2))

Module(

body=[

Assign(

targets=[

Name(id='x', ctx=Store())],

value=List(

elts=[

Constant(value=1),

Constant(value=2)],

ctx=Load())),

Expr(

value=Call(

func=Name(id='print', ctx=Load()),

args=[

Name(id='x', ctx=Load())],

keywords=[]))],

type_ignores=[])It might seem a bit too much at first, but let me break it down.

The AST is taken as a python module (the same as a Python file in this case).

>>> print(ast.dump(tree, indent=2))

Module(

body=[

...The module's body has two children (two statements):

-

The first is an

Assignstatement...Assign( ...Which assigns to the target

x...targets=[ Name(id='x', ctx=Store())], ...The value of a

listwith 2 constants1and2.value=List( elts=[ Constant(value=1), Constant(value=2)], ctx=Load())), ), -

The second is an

Exprstatement, which in this case is a function call...Expr( value=Call( ...Of the name

print, with the valuex.func=Name(id='print', ctx=Load()), args=[ Name(id='x', ctx=Load())],

So the Assign part is describing x = [1, 2] and the Expr is describing print(x). Doesn't seem that bad now, right?

Extras: the Tokenizer

There's actually one step that occurs before parsing the code into an AST: Lexing.

This refers to converting the source code into tokens, based on Python's grammar. You can take a look at how Python tokenizes your files, you can use the tokenize module:

$ cat code.py

x = [1, 2]

print(x)

$ py -m tokenize code.py

0,0-0,0: ENCODING 'utf-8'

1,0-1,1: NAME 'x'

1,2-1,3: OP '='

1,4-1,5: OP '['

1,5-1,6: NUMBER '1'

1,6-1,7: OP ','

1,8-1,9: NUMBER '2'

1,9-1,10: OP ']'

1,10-1,11: NEWLINE '\n'

2,0-2,5: NAME 'print'

2,5-2,6: OP '('

2,6-2,7: NAME 'x'

2,7-2,8: OP ')'

2,8-2,9: NEWLINE '\n'

3,0-3,0: ENDMARKER ''It has converted our file into its bare tokens, things like variable names, brackets, strings and numbers. It also keeps track of the line numbers and locations of each token, which helps in pointing at the exact location of an error message, for example.

This "token stream" is what's parsed into an AST.

So now we have an AST object. We can compile it into a code object using the compile builtin. Running exec on the code object will then run it just as before:

>>> import ast

>>> code = '''

... x = [1, 2]

... print(x)

... '''

>>> tree = ast.parse(code)

>>> code_obj = compile(tree, 'myfile.py', 'exec')

>>> exec(code_obj)

[1, 2]But now, we can look into what a code object looks like. Let's examine some of its properties:

>>> code_obj.co_code

b'd\x00d\x01g\x02Z\x00e\x01e\x00\x83\x01\x01\x00d\x02S\x00'

>>> code_obj.co_filename

'myfile.py'

>>> code_obj.co_names

('x', 'print')

>>> code_obj.co_consts

(1, 2, None)You can see that the variables x and print used in the code, as well as the constants 1 and 2, plus a lot more information about our code file is available inside the code object. This has all the information needed to directly run in the Python virtual machine, in order to produce that output.

If you want to dive deep into what the bytecode means, the extras section below on the dis module will cover that.

Extras: the "dis" module

The dis module in Python can be used to visualize the contents of code objects in a human-understandable way, to help figure out what Python is doing under the hood. It takes in the bytecode, constant and variable information, and produces this:

>>> import dis

>>> dis.dis('''

... x = [1, 2]

... print(x)

... ''')

1 0 LOAD_CONST 0 (1)

2 LOAD_CONST 1 (2)

4 BUILD_LIST 2

6 STORE_NAME 0 (x)

2 8 LOAD_NAME 1 (print)

10 LOAD_NAME 0 (x)

12 CALL_FUNCTION 1

14 POP_TOP

16 LOAD_CONST 2 (None)

18 RETURN_VALUE

>>>It shows that:

- Line 1 creates 4 bytecodes, to load 2 constants

1and2onto the stack, build a list from the top2values on the stack, and store it into the variablex. - Line 2 creates 6 bytecodes, it loads

printandxonto the stack, and calls the function on the stack with the1argument on top of it (Meaning, it callsprintwith argumentx). Then it gets rid of the return value from the call by doingPOP_TOPbecause we didn't use or store the return value fromprint(x). The two lines at the end returnsNonefrom the end of the file's execution, which does nothing.

Each of these bytecodes is 2 bytes long when stored as "opcodes" (the names that you are seeing, LOAD_CONST for example, are opcodes), that's why the numbers to the left of the opcodes are 2 away from each other. It also shows that this entire code is 20 bytes long. And indeed, if you do:

>>> code_obj = compile('''

... x = [1, 2]

... print(x)

... ''', 'test', 'exec')

>>> code_obj.co_code

b'd\x00d\x01g\x02Z\x00e\x01e\x00\x83\x01\x01\x00d\x02S\x00'

>>> len(code_obj.co_code)

20You can confirm that the bytecode generated is exactly 20 bytes.

eval is pretty similar to exec, except it only accepts expressions (not statements or a set of statements like exec), and unlike exec, it returns a value -- the result of said expression.

Here's an example:

>>> result = eval('1 + 1')

>>> result

2You can also go the long, detailed route with eval, you just need to tell ast.parse and compile that you're expecting to evaluate this code for its value, instead of running it like a Python file.

>>> expr = ast.parse('1 + 1', mode='eval')

>>> code_obj = compile(expr, '<code>', 'eval')

>>> eval(code_obj)

2globals and locals: Where everything is stored

While the code objects produced store the logic as well as constants defined within a piece of code, one thing that they don't (or even can't) store, is the actual values of the variables being used.

There's a few reasons for this concerning how the language works, but the most obvious reason can be seen very simply:

def double(number):

return number * 2The code object of this function will store the constant 2, as well as the variable name number, but it obviously cannot contain the actual value of number, as that isn't given to it until the function is actually run.

So where does that come from? The answer is that Python stores everything inside dictionaries associated with each local scope. Which means that every piece of code has its own defined "local scope" which is accessed using locals() inside that code, that contains the values corresponding to each variable name.

Let's try to see that in action:

>>> value = 5

>>> def double(number):

... return number * 2

...

>>> double(value)

10

>>> locals()

{'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': None,

'__loader__': <class '_frozen_importlib.BuiltinImporter'>, '__spec__': None,

'__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>,

'value': 5, 'double': <function double at 0x7f971d292af0>}Take a look at the last line: not only is value stored inside the locals dictionary, the function double itself is stored there as well! So that's how Python stores its data.

globals is pretty similar, except that globals always points to the module scope (also known as global scope). So with something like this code:

magic_number = 42

def function():

x = 10

y = 20

print(locals())

print(globals())locals would just contain x and y, while globals would contain magic_number and function itself.

input and print: The bread and butter

input and print are probably the first two functionalities that you learn about Python. And they seem pretty straightforward, don't they? input takes in a line of text, and print prints it out, simple as that. Right?

Well, input and print have a bit more functionality than what you might know about.

Here's the full method signature of print:

print(*values, sep=' ', end='\n', file=sys.stdout, flush=False)The *values simply means that you can provide any number of positional arguments to print, and it will properly print them out, separated with spaces by default.

If you want the separator to be different, for eg. if you want each item to be printed on a different line, you can set the sep keyword accordingly, like '\n':

>>> print(1, 2, 3, 4)

1 2 3 4

>>> print(1, 2, 3, 4, sep='\n')

1

2

3

4

>>> print(1, 2, 3, 4, sep='\n\n')

1

2

3

4

>>>There's also an end parameter, if you want a different character for line ends, like, if you don't want a new line to be printed at the end of each print, you can use end='':

>>> for i in range(10):

... print(i)

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

>>> for i in range(10):

... print(i, end='')

0123456789Now there's two more parameters to print: file and flush.

file refers to the "file" that you are printing to. By default it points to sys.stdout, which is a special "file" wrapper, that prints to the console. But if you want print to write to a file instead, all you have to do is change the file parameter. Something like:

with open('myfile.txt', 'w') as f:

print('Hello!', file=f)Extras: using a context manager to make a print-writer

Some languages have special objects that let you call print method on them, to write to a file by using the familiar "print" interface. In Python, you can go a step beyond that: you can temporarily configure the print function to write to a file by default!

This is done by re-assigning sys.stdout. If we swap out the file that sys.stdout is assigned to, then all print statements magically start printing to that file instead. How cool is that?

Let's see with an example:

>>> import sys

>>> print('a regular print statement')

a regular print statement

>>> file = open('myfile.txt', 'w')

>>> sys.stdout = file

>>> print('this will write to the file') # Gets written to myfile.txt

>>> file.close()But, there's a problem here. We can't go back to printing to console this way. And even if we store the original stdout, it would be pretty easy to mess up the state of the sys module by accident.

For example:

>>> import sys

>>> print('a regular print statement')

a regular print statement

>>> file = open('myfile.txt', 'w')

>>> sys.stdout = file

>>> file.close()

>>> print('this will write to the file')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 2, in <module>

ValueError: I/O operation on closed file.To avoid accidentally leaving the sys module in a broken state, we can use a context manager, to ensure that sys.stdout is restored when we are done.

import sys

from contextlib import contextmanager

@contextmanager

def print_writer(file_path):

original_stdout = sys.stdout

with open(file_path, 'w') as f:

sys.stdout = f

yield # this is where everything inside the `with` statement happens

sys.stdout = original_stdoutThat's it! And here's how you would use it:

with print_writer('myfile.txt'):

print('Printing straight to the file!')

for i in range(5):

print(i)

print('and regular print still works!')Sending prints to files or IO objects is a common enough use-case that contextlib has a pre-defined function for it, called redirect_stdout:

from contextlib import redirect_stdout

with open('this.txt', 'w') as file:

with redirect_stdout(file):

import this

with open('this.txt') as file:

print(file.read())

# Output:

# The Zen of Python, by Tim Peters

# ...flush is a boolean flag to the print function. All it does is tell print to write the text immediately to the console/file instead of putting it in a buffer. This usually doesn't make much of a difference, but if you're printing a very large string to a console, you might want to set it to True

to avoid lag in showing the output to the user.

Now I'm sure many of you are interested in what secrets the input function hides, but there's none. input simply takes in a string to show as the prompt. Yeah, bummer, I know.

str, bytes, int, bool, float and complex: The five primitives

Python has exactly 6 primitive data types (well, actually just 5, but we'll get to that). 4 of these are numerical in nature, and the other 2 are text-based. Let's talk about the text-based first, because that's going to be much simpler.

str is one of the most familiar data types in Python. Taking user input using the input method gives you a string, and every other data type in Python can be converted into a string. This is necessary because all computer Input/Output is in text-form, be it user I/O or file I/O, which is probably why strings are everywhere.

bytes on the other hand, are actually the basis of all I/O in computing. If you know about computers, you would probably know that all data is stored and handled as bits and bytes -- and that's how terminals really work as well.

If you want to take a peek at the bytes underneath the input and print calls: you need to take a look at the I/O buffers in the sys module: sys.stdout.buffer and sys.stdin.buffer:

>>> import sys

>>> print('Hello!')

Hello!

>>> 'Hello!\n'.encode() # Produces bytes

b'Hello!\n'

>>> char_count = sys.stdout.buffer.write('Hello!\n'.encode())

Hello!

>>> char_count # write() returns the number of bytes written to console

7The buffer objects take in bytes, write those directly to the output buffer, and return the number of bytes returned.

To prove that everything is just bytes underneath, let's look at another example that prints an emoji using its bytes:

>>> import sys

>>> '🐍'.encode()

b'\xf0\x9f\x90\x8d' # utf-8 encoded string of the snake emoji

>>> _ = sys.stdout.buffer.write(b'\xf0\x9f\x90\x8d')

🐍int is another widely-used, fundamental primitive data type. It's also the lowest common denominator of 2 other data types: , float and complex. complex is a supertype of float, which, in turn, is a supertype of int.

What this means is that all ints are valid as a float as well as a complex, but not the other way around. Similarly, all floats are also valid as a complex.

If you don't know,

complexis the implementation for "complex numbers" in Python. They're a really common tool in mathematics.

Let's take a look at them:

>>> x = 5

>>> y = 5.0

>>> z = 5.0+0.0j

>>> type(x), type(y), type(z)

(<class 'int'>, <class 'float'>, <class 'complex'>)

>>> x == y == z # All the same value

True

>>> y

5.0

>>> float(x) # float(x) produces the same result as y

5.0

>>> z

(5+0j)

>>> complex(x) # complex(x) produces the same result as z

(5+0j)Now, I mentioned for a moment that there's actually only 5 primitive data types in Python, not 6. That is because, bool is actually not a primitive data type -- it's actually a subclass of int!

You can check it yourself, by looking into the mro property of these classes.

mro stands for "method resolution order". It defines the order in which the methods called on a class are looked for. Essentially, the method calls are first looked for in the class itself, and if it's not present there, it's searched in its parent class, and then its parent, all the way to the top: object. Everything in Python inherits from object. Yes, pretty much everything in Python is an object.

Take a look:

>>> int.mro()

[<class 'int'>, <class 'object'>]

>>> float.mro()

[<class 'float'>, <class 'object'>]

>>> complex.mro()

[<class 'complex'>, <class 'object'>]

>>> str.mro()

[<class 'str'>, <class 'object'>]

>>> bool.mro()

[<class 'bool'>, <class 'int'>, <class 'object'>] # Look!You can see from their "ancestry", that all the other data types are not "sub-classes" of anything (except for object, which will always be there). Except bool, which inherits from int.

Now at this point, you might be wondering "WHY? Why does bool subclass int?" And the answer is a bit anti-climatic. It's mostly because of compatibility reasons. Historically, logical true/false operations in Python simply used 0 for false and 1 for true. In Python version 2.2, the boolean values True and False were added to Python, and they were simply wrappers around these integer values. The fact has stayed the same till date. That's all.

But, it also means that, for better or for worse, you can pass a bool wherever an int is expected:

>>> import json

>>> data = {'a': 1, 'b': {'c': 2}}

>>> print(json.dumps(data))

{"a": 1, "b": {"c": 2}}

>>> print(json.dumps(data, indent=4))

{

"a": 1,

"b": {

"c": 2

}

}

>>> print(json.dumps(data, indent=True))

{

"a": 1,

"b": {

"c": 2

}

}indent=True here is treated as indent=1, so it works, but I'm pretty sure nobody would intend that to mean an indent of 1 space. Welp.

object: The base

object is the base class of the entire class hierarchy. Everyone inherits from object.

The object class defines some of the most fundamental properties of objects in Python. Functionalities like being able to hash an object through hash(), being able to set attributes and get their value, being able to convert an object into a string representation, and many more.

It does all of this through its pre-defined "magic methods":

>>> dir(object)

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__',

'__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__le__',

'__lt__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__',

'__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__']Accessing an attribute with obj.x calls the __getattr__ method underneath. Similarly setting a new attribute and deleting an attribute calls __setattr__ and __delattr__ respectively. The object's hash is generated by the pre-defined __hash__ method, and the string representation of objects comes from __repr__.

>>> object() # This creates an object with no properties

<object object at 0x7f47aecaf210> # defined in __repr__()

>>> class dummy(object):

... pass

>>> x = dummy()

>>> x

<__main__.dummy object at 0x7f47aec510a0> # functionality inherited from object

>>> hash(object())

8746615746334

>>> hash(x)

8746615722250

>>> x.__hash__() # is the same as hash(x)

8746615722250There's actually a lot more to speak about magic methods in Python, as they form the backbone of the object-oriented, duck-typed nature of Python. But, that's a story for another blog.

Stay tuned if you're interested 😉

type: The class factory

If object is the father of all objects, type is father of all "classes". As in, while all objects inherit from object, all classes inherit from type.

type is the builtin that can be used to dynamically create new classes. Well, it actually has two uses:

-

If given a single parameter, it returns the "type" of that parameter, i.e. the class used to make that object:

>>> x = 5 >>> type(x) <class 'int'> >>> type(x) is int True >>> type(x)(42.0) # Same as int(42.0) 42 -

If given three parameters, it creates a new class. The three parameters are

name,bases, anddict.namedefines the name of the classbasesdefines the base classes, i.e. superclassesdictdefines all class attributes and methods.

So this class definition:

class MyClass(MySuperClass): def x(self): print('x')Is identical to this class definition:

def x_function(self): print('x') MyClass = type('MyClass', (MySuperClass,), {'x': x_function})This can be one way to implement the

collections.namedtupleclass, for example, which takes in a class name and a tuple of attributes.

hash and id: The equality fundamentals

The builtin functions hash and id make up the backbone of object equality in Python.

Python objects by default aren't comparable, unless they are identical. If you try to create two object() items and check if they're equal...

>>> x = object()

>>> y = object()

>>> x == x

True

>>> y == y

True

>>> x == y # Comparing two objects

FalseThe result will always be False. This comes from the fact that objects compare themselves by identity: They are only equal to themselves, nothing else.

Extras: Sentinels

For this reason, object instances are also sometimes called a "sentinel", because they can be used to check for a value exactly, that can't be replicated.

A nice use-case of sentinel values comes in a case where you need to provide a default value to a function where every possible value is a valid input. A really silly example would be this behaviour:

>>> what_was_passed(42)

You passed a 42.

>>> what_was_passed('abc')

You passed a 'abc'.

>>> what_was_passed()

Nothing was passed.And at first glance, being able to write this code out would be pretty simple:

def what_was_passed(value=None):

if value is None:

print('Nothing was passed.')

else:

print(f'You passed a {value!r}.')But, this doesn't work. What about this:

>>> what_was_passed(None)

Nothing was passed.Uh oh. We can't explicitly pass a None to the function, because that's the default value. We can't really use any other literal or even ... Ellipsis, because those won't be able to be passed then.

This is where a sentinel comes in:

__my_sentinel = object()

def what_was_passed(value=__my_sentinel):

if value is __my_sentinel:

print('Nothing was passed.')

else:

print(f'You passed a {value!r}.')And now, this will work for every possible value passed to it.

>>> what_was_passed(42)

You passed a 42.

>>> what_was_passed('abc')

You passed a 'abc'.

>>> what_was_passed(None)

You passed a None.

>>> what_was_passed(object())

You passed a <object object at 0x7fdf02f3f220>.

>>> what_was_passed()

Nothing was passed.To understand why objects only compare to themselves, we will have to understand the is keyword.

Python's is operator is used to check if two values reference the same exact object in memory. Think of Python objects like boxes floating around in space, and variables, array indexes, and so on being named arrows pointing to these objects.

Let's take a quick example:

>>> x = object()

>>> y = object()

>>> z = y

>>> x is y

False

>>> y is z

TrueIn the code above, there are two separate objects, and three labels x, y and z pointing to these two objects: x pointing to the first one, and y and z both pointing to the other one.

>>> del xThis deletes the arrow x. The objects themselves aren't affected by assignment, or deletion, only the arrows are. But now that there are no arrows pointing to the first object, it is meaningless to keep it alive. So Python's "garbage collector" gets rid of it. Now we are left with a single object.

>>> y = 5Now y arrow has been changed to point to an integer object 5 instead. z still points to the second object though, so it's still alive.

>>> z = y * 2Now z points to yet another new object 10, which is stored somewhere in memory. Now the second object also has nothing pointing to it, so that is subsequently garbage collected.

To be able to verify all of this, we can use the id builtin function. id spells out a number that uniquely identifies the object during its lifetime. In CPython that’s the exact memory location of that object, but this is an implementation detail and other interpreters may choose a different representation.

>>> x = object()

>>> y = object()

>>> z = y

>>> id(x)

139737240793600

>>> id(y)

139737240793616

>>> id(z)

139737240793616 # Notice the numbers!

>>> x is y

False

>>> id(x) == id(y)

False

>>> y is z

True

>>> id(y) == id(z)

TrueSame object, same id. Different objects, different id. Simple as that.

Extra: Small Integer Cache & String Interning

First, some intriguing yet confusing code.

>>> x = 1

>>> id(x)

136556405979440

>>> y = 1

>>> id(y)

136556405979440 # same int object?

>>> x = 257

>>> id(x)

136556404964368

>>> y = 257

>>> id(y)

136556404964144 # but different int object now???

>>> x = "hello"

>>> id(x)

136556404561904

>>> y = "hello"

>>> id(y)

136556404561904 # same str object?Integers and strings are objects that are used in almost any program, and in many cases there are copies of the same integer value or the same string content. To save the time and memory of creating a whole new object when an exact same one is already there, CPython implements two common techniques used in many other languages: Small Integer Cache & String Interning.

Although they have different names, the underlying idea is the same: make objects immutable and reuse them across different references (arrows). Small Integer Cache makes integers in the range of [-5,256] reuse the same object for the same value. String Interning points references to strings having the same content to the same object.

This is just a simplified explanation, and you should read more if you care about the memory consumption of your Python program. Hopefully the code example makes sense to you now.

With objects, == and is behaves the same way:

>>> x = object()

>>> y = object()

>>> z = y

>>> x is y

False

>>> x == y

False

>>> y is z

True

>>> y == z

TrueThis is because object's behaviour for == is defined to compare the id. Something like this:

class object:

def __eq__(self, other):

return self is otherThe actual implementation of object is written in C.

Unlike

==, there's no way to override the behavior of theisoperator.

Container types, on the other hand, are equal if they can be replaced with each other. Good examples would be lists which have the same items at the same indices, or sets containing the exact same values.

>>> x = [1, 2, 3]

>>> y = [1, 2, 3]

>>> x is y

False # Different objects,

>>> x == y

True # Yet, equal.These can be defined in this way:

class list:

def __eq__(self, other):

if len(self) != len(other):

return False

return all(x == y for x, y in zip(self, other))

# Can also be written as:

return all(self[i] == other[i] for i in range(len(self)))We haven't looked at

allorzipyet, but all this does is make sure all of the given list indices are equal.

Similarly, sets are unordered so even their location doesn't matter, only their "presence":

class set:

def __eq__(self, other):

if len(self) != len(other):

return False

return all(item in other for item in self)Now, related to the idea of "equivalence", Python has the idea of hashes. A "hash" of any piece of data refers to a pre-computed value that looks pretty much random, but it can be used to identify that piece of data (to some extent).

Hashes have two specific properties:

- The same piece of data will always have the same hash value.

- Changing the data even very slightly, returns in a drastically different hash.

What this means is that if two values have the same hash, it's very *likely* that they have the same value as well.

Comparing hashes is a really fast way to check for "presence". This is what dictionaries and sets use to find values inside them pretty much instantly:

>>> import timeit

>>> timeit.timeit('999 in l', setup='l = list(range(1000))')

12.224023487000522 # 12 seconds to run a million times

>>> timeit.timeit('999 in s', setup='s = set(range(1000))')

0.06099735599855194 # 0.06 seconds for the same thingNotice that the set solution is running hunderds of times faster than the list solution! This is because they use the hash values as their replacement for "indices", and if a value at the same hash is already stored in the set/dictionary, Python can quickly check if it's the same item or not. This process makes checking for presence pretty much instant.

Extras: hash factoids

Another little-known fact about hashes is that in Python, all numeric values that compare equal have the same hash:

>>> hash(42) == hash(42.0) == hash(42+0j)

TrueAnother factoid is that immutable container objects such as strings (strings are a sequence of strings), tuples and frozensets, generate their hash by combining the hashes of their items. This allows you to create custom hash functions for your classes simply by composing the hash function:

class Car:

def __init__(self, color, wheels=4):

self.color = color

self.wheels = wheels

def __hash__(self):

return hash((self.color, self.wheels))dir and vars: Everything is a dictionary

Have you ever wondered how Python stores objects, their variables, their methods and such? We know that all objects have their own properties and methods attached to them, but how exactly does Python keep track of them?

The simple answer is that everything is stored inside dictionaries. And the vars method exposes the variables stored inside objects and classes.

>>> class C:

... some_constant = 42

... def __init__(self, x, y):

... self.x = x

... self.y = y

... def some_method(self):

... pass

...

>>> c = C(x=3, y=5)

>>> vars(c)

{'x': 3, 'y': 5}

>>> vars(C)

mappingproxy(

{'__module__': '__main__', 'some_constant': 42,

'__init__': <function C.__init__ at 0x7fd27fc66d30>,

'some_method': <function C.some_method at 0x7fd27f350ca0>,

'__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'C' objects>,

'__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'C' objects>,

'__doc__': None

})As you can see, the attributes x and y related to the object c are stored in its own dictionary, and the methods (some_function and __init__) are actually stored as functions in the class's dictionary. Which makes sense, as the code of the function itself doesn't change for every object, only the variables passed to it change.

This can be demonstrated with the fact that c.method(x) is the same as C.method(c, x):

>>> class C:

... def function(self, x):

... print(f'self={self}, x={x}')

>>> c = C()

>>> C.function(c, 5)

self=<__main__.C object at 0x7f90762461f0>, x=5

>>> c.function(5)

self=<__main__.C object at 0x7f90762461f0>, x=5It shows that a function defined inside a class really is just a function, with self being just an object that is passed as the first argument. The object syntax c.method(x) is just a cleaner way to write C.method(c, x).

Now here's a slightly different question. If vars shows all methods inside a class, then why does this work?

>>> class C:

... def function(self, x): pass

...

>>> vars(C)

mappingproxy({

'__module__': '__main__',

'function': <function C.function at 0x7f607ddedb80>,

'__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'C' objects>,

'__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'C' objects>,

'__doc__': None

})

>>> c = C()

>>> vars(c)

{}

>>> c.__class__

<class '__main__.C'>🤔 __class__ is defined in neither c's dict, nor in C... then where is it coming from?

If you want a definitive answer of which properties can be accessed on an object, you can use dir:

>>> dir(c)

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__',

'__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__',

'__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__module__', '__ne__', '__new__',

'__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__',

'__subclasshook__', '__weakref__', 'function']So where are the rest of the properties coming from? Well, the story is slightly more complicated, for one simple reason: Python supports inheritance.

All objects in python inherit by default from the object class, and indeed, __class__ is defined on object:

>>> '__class__' in vars(object)

True

>>> vars(object).keys()

dict_keys(['__repr__', '__hash__', '__str__', '__getattribute__', '__setattr__',

'__delattr__', '__lt__', '__le__', '__eq__', '__ne__', '__gt__', '__ge__',

'__init__', '__new__', '__reduce_ex__', '__reduce__', '__subclasshook__',

'__init_subclass__', '__format__', '__sizeof__', '__dir__', '__class__', '__doc__'])And that does cover everything that we see in the output of dir(c).

Now that I've mentioned inheritence, I think I should also elaborate how the "method resolution order" works. MRO for short, this is the list of classes that an object inherits properties and methods from. Here's a quick example:

>>> class A:

... def __init__(self):

... self.x = 'x'

... self.y = 'y'

...

>>> class B(A):

... def __init__(self):

... super().__init__()

... self.z = 'z'

...

>>> a = A()

>>> b = B()

>>> B.mro()

[<class '__main__.B'>, <class '__main__.A'>, <class 'object'>]

>>> dir(b)

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__',

'__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__',

'__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__module__', '__ne__', '__new__',

'__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__',

'__subclasshook__', '__weakref__', 'x', 'y', 'z']

>>> set(dir(b)) - set(dir(a)) # all values in dir(b) that are not in dir(a)

{'z'}

>>> vars(b).keys()

dict_keys(['z'])

>>> set(dir(a)) - set(dir(object))

{'x', 'y'}

>>> vars(a).keys()

dict_keys(['x', 'y'])So every level of inheritence adds the newer methods into the dir list, and dir on a subclass shows all methods found in its method resolution order. And that's how Python suggests method completion in the REPL:

>>> class A:

... x = 'x'

...

>>> class B(A):

... y = 'y'

...

>>> b = B()

>>> b. # Press <tab> twice here

b.x b.y # autocompletion!Extras: slots?

__slots__ are interesting.

Here's one weird/interesting behaviour that Python has:

>>> x = object()

>>> x.foo = 5

AttributeError: 'object' object has no attribute 'foo'

>>> class C:

... pass

...

>>> c = C()

>>> c.foo = 5

>>> # works?So, for some reason you can't assign arbitrary variables to object, but you can to an object of a class that you yourself created. Why could that be? Is it specific to object?

>>> x = list()

>>> x.foo = 5

AttributeError: 'list' object has no attribute 'foo'Nope. So what's going on?

Well, This is where slots come in. Firstly, let me replicate the behaviour shown by list and object in my own class:

>>> class C:

... __slots__ = ()

...

>>> c = C()

>>> c.foo = 5

AttributeError: 'C' object has no attribute 'foo'Now here's the long explanation:

Python actually has two ways of storing data inside objects: as a dictionary (like most cases), and as a "struct". Structs are a C language data type, which can essentially be thought of as tuples from Python. Dictionaries use more memory, because they can be expanded as much as you like and rely on extra space for their reliability in quickly accessing data, that's just how dictionaries are. Structs on the other hand, have a fixed size, and cannot be expanded, but they take the least amount of memory possible as they pack those values one after the other without any wasted space.

These two ways of storing data in Python are reflected by the two object properties __dict__ and __slots__. Normally, all instance attributes (self.foo) are stored inside __dict__ the dictionary, unless you define the __slots__ attribute, in which case the object can only have a constant number of pre-defined attributes.

I can understand if this is getting too confusing. Let me just show an example:

>>> class NormalClass:

... classvar = 'foo'

... def __init__(self):

... self.x = 1

... self.y = 2

...

>>> n = NormalClass()

>>> n.__dict__

{'x': 1, 'y': 2} # Note that `classvar` variable isn't here.

>>> # That is stored in `NormalClass.__dict__`

>>> class SlottedClass:

... __slots__ = ('x', 'y')

... classvar = 'foo' # This is fine.

... def __init__(self):

... self.x = 1

... self.y = 2

... # Trying to create `self.z` here will cause the same

... # `AttributeError` as before.

...

>>> s = SlottedClass()

>>> s.__dict__

AttributeError: 'SlottedClass' object has no attribute '__dict__'

>>> s.__slots__

('x', 'y')So creating slots prevents a __dict__ from existing, which means no dictionary to add new attributes into, and it also means saved memory. That's basically it.

AnthonyWritesCode made a video about another interesting piece of code relating to slots and their obscure behaviour, do check that out!

hasattr, getattr, setattr and delattr: Attribute helpers

Now that we've seen that objects are pretty much the same as dictionaries underneath, let's draw a few more paralells between them while we are at it.

We know that accessing as well as reassigning a property inside a dictionary is done using indexing:

>>> dictionary = {'property': 42}

>>> dictionary['property']

42while on an object it is done via the . operator:

>>> class C:

... prop = 42

...

>>> C.prop

42You can even set and delete properties on objects:

>>> C.prop = 84

>>> C.prop

84

>>> del C.prop

>>> C.prop

AttributeError: type object 'C' has no attribute 'prop'But dictionaries are so much more flexible: you can for example, check if a property exists in a dictionary:

>>> d = {}

>>> 'prop' in d

False

>>> d['prop'] = 'exists'

>>> 'prop' in d

TrueYou could do this in an object by using try-catch:

>>> class X:

... pass

...

>>> x = X()

>>> try:

... print(x.prop)

>>> except AttributeError:

... print("prop doesn't exist.")

prop doesn't exist.But the preferred method to do this would be direct equivalent: hasattr.

>>> class X:

... pass

...

>>> x = X()

>>> hasattr(x, 'prop')

False

>>> x.prop = 'exists'

>>> hasattr(x, 'prop')

TrueAnother thing that dictionaries can do is using a variable to index a dict. You can't really do that with objects, right? Let's try:

>>> class X:

... value = 42

...

>>> x = X()

>>> attr_name = 'value'

>>> x.attr_name

AttributeError: 'X' object has no attribute 'attr_name'Yeah, it doesn't take the variable's value. This should be pretty obvious. But to actually do this, you can use getattr, which does take in a string, just like a dictionary key:

>>> class X:

... value = 42

...

>>> x = X()

>>> getattr(x, 'value')

42

>>> attr_name = 'value'

>>> getattr(x, attr_name)

42 # It works!setattr and delattr work the same way: they take in the attribute name as a string, and sets/deletes the corresponding attribute accordingly.

>>> class X:

... def __init__(self):

... value = 42

...

>>> x = X()

>>> setattr(x, 'value', 84)

>>> x.value

84

>>> delattr(x, 'value') # deletes the attribute completety

>>> hasattr(x, 'value')

False # `value` no longer exists on the object.Let's try to build something that kinda makes sense with one of these functions:

Sometimes you need to create a function that has to be overloaded to either take a value directly, or take a "factory" object, it can be an object or a function for example, which generates the required value on demand. Let's try to implement that pattern:

class api:

"""A dummy API."""

def send(item):

print(f'Uploaded {item!r}!')

def upload_data(item):

"""Uploads the provided value to our database."""

if hasattr(item, 'get_value'):

data = item.get_value()

api.send(data)

else:

api.send(item)The upload_data function is checking if we have gotten a factory object, by checking if it has a get_value method. If it does, that function is used to get the actual value to upload. Let's try to use it!

>>> import json

>>> class DataCollector:

... def __init__(self):

... self.items = []

... def add_item(self, item):

... self.items.append(item)

... def get_value(self):

... return json.dumps(self.items)

...

>>> upload_data('some text')

Uploaded 'some text'!

>>> collector = DataCollector()

>>> collector.add_item(42)

>>> collector.add_item(1000)

>>> upload_data(collector)

Uploaded '[42, 1000]'!super: The power of inheritance

super is Python's way of referencing a superclass, to use its methods, for example.

Take this example, of a class that encapsulates the logic of summing two items:

class Sum:

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def perform(self):

return self.x + self.yUsing this class is pretty simple:

>>> s = Sum(2, 3)

>>> s.perform()

5Now let's say you want to subclass Sum to create a a DoubleSum class, which has the same perform interface but it returns double the value instead. You'd use super for that:

class DoubleSum(Sum):

def perform(self):

parent_sum = super().perform()

return 2 * parent_sumWe didn't need to define anything that was already defined: We didn't need to define __init__, and we didn't have to re-write the sum logic as well. We simply piggy-backed on top of the superclass.

>>> d = DoubleSum(3, 5)

>>> d.perform()

16Now there are some other ways to use the super object, even outside of a class:

>>> super(int)

<super: <class 'int'>, NULL>

>>> super(int, int)

<super: <class 'int'>, <int object>>

>>> super(int, bool)

<super: <class 'int'>, <bool object>>But honestly, I don't understand what these would ever be used for. If you know, let me know in the comments ✨

property, classmethod and staticmethod: Method decorators

We're reaching the end of all the class and object-related builtin functions, the last of it being these three decorators.

-

property:@propertyis the decorator to use when you want to define getters and setters for properties in your object. Getters and setters provide a way to add validation or run some extra code when trying to read or modify the attributes of an object.This is done by turning the property into a set of functions: one function that is run when you try to access the property, and another that is run when you try to change its value.

Let's take a look at an example, where we try to ensure that the "marks" property of a student is always set to a positive number, as marks cannot be negative:

class Student: def __init__(self): self._marks = 0 @property def marks(self): return self._marks @marks.setter def marks(self, new_value): # Doing validation if new_value < 0: raise ValueError('marks cannot be negative') # before actually setting the value. self._marks = new_valueRunning this code:

>>> student = Student() >>> student.marks 0 >>> student.marks = 85 >>> student.marks 85 >>> student.marks = -10 ValueError: marks cannot be negative -

classmethod:@classmethodcan be used on a method to make it a class method instead: such that it gets a reference to the class object, instead of the instance (self).A simple example would be to create a function that returns the name of the class:

>>> class C: ... @classmethod ... def class_name(cls): ... return cls.__name__ ... >>> x = C() >>> x.class_name() 'C' -

staticmethod:@staticmethodis used to convert a method into a static method: one equivalent to a function sitting inside a class, independent of any class or object properties. Using this completely gets rid of the firstselfargument passed to methods.We could make one that does some data validation for example:

class API: @staticmethod def is_valid_title(title_text): """Checks whether the string can be used as a blog title.""" return title_text.istitle() and len(title_text) < 60

These builtins are created using a pretty advanced topic called descriptors. I'll be honest, descriptors are a topic that is so advanced that trying to cover it here won't be of any use beyond what has already been told. I'm planning on writing a detailed article on descriptors and their uses sometime in the future, so stay tuned for that!

list, tuple, dict, set and frozenset: The containers

A "container" in Python refers to a data structure that can hold any number of items inside it.

Python has 5 fundamental container types:

-

list: Ordered, indexed container. Every element is present at a specific index. Lists are mutable, i.e. items can be added or removed at any time.>>> my_list = [10, 20, 30] # Creates a list with 3 items >>> my_list[0] # Indexes start with zero 10 >>> my_list[1] # Indexes increase one by one 20 >>> my_list.append(40) # Mutable: can add values >>> my_list [10, 20, 30, 40] >>> my_list[0] = 50 # Can also reassign indexes >>> my_list [50, 20, 30, 40] -

tuple: Ordered and indexed just like lists, but with one key difference: They are immutable, which means items cannot be added or deleted once the tuple is created.>>> some_tuple = (1, 2, 3) >>> some_tuple[0] # Indexable 1 >>> some_tuple.append(4) # But NOT mutable AttributeError: ... >>> some_tuple[0] = 5 # Cannot reassign an index as well TypeError: ... -

dict: Unordered key-value pairs. The key is used to access the value. Only one value can correspond to a given key.>>> flower_colors = {'roses': 'red', 'violets': 'blue'} >>> flower_colors['violets'] # Use keys to access value 'blue' >>> flower_colors['violets'] = 'purple' # Mutable >>> flower_colors {'roses': 'red', 'violets': 'purple'} >>> flower_colors['daffodil'] = 'yellow' # Can also add new values >>> flower_colors {'roses': 'red', 'violets': 'purple', 'daffodil': 'yellow'} -

set: Unordered, unique collection of data. Items in a set simply represent their presence or absence. You could use a set to find for example, the kinds of trees in a forest. Their order doesn't matter, only their existance.>>> forest = ['cedar', 'bamboo', 'cedar', 'cedar', 'cedar', 'oak', 'bamboo'] >>> tree_types = set(forest) >>> tree_types {'bamboo', 'oak', 'cedar'} # Only unique items >>> 'oak' in tree_types True >>> tree_types.remove('oak') # Sets are also mutable >>> tree_types {'bamboo', 'cedar'} -

A

frozensetis identical to a set, but just liketuples, is immutable.>>> forest = ['cedar', 'bamboo', 'cedar', 'cedar', 'cedar', 'oak', 'bamboo'] >>> tree_types = frozenset(forest) >>> tree_types frozenset({'bamboo', 'oak', 'cedar'}) >>> 'cedar' in tree_types True >>> tree_types.add('mahogany') # CANNOT modify AttributeError: ...

The builtins list, tuple and dict can be used to create empty instances of these data structures too:

>>> x = list()

>>> x

[]

>>> y = dict()

>>> y

{}But the short-form {...} and [...] is more readable and should be preferred. It's also a tiny-bit faster to use the short-form syntax, as list, dict etc. are defined inside builtins, and looking up these names inside the variable scopes takes some time, whereas [] is understood as a list without any lookup.

bytearray and memoryview: Better byte interfaces

A bytearray is the mutable equivalent of a bytes object, pretty similar to how lists are essentially mutable tuples.

bytearray makes a lot of sense, as:

-

A lot of low-level interactions have to do with byte and bit manipulation, like this horrible implementation for

str.upper, so having a byte array where you can mutate individual bytes is going to be much more efficient. -

Bytes have a fixed size (which is... 1 byte). On the other hand, string characters can have various sizes thanks to the unicode encoding standard, "utf-8":

>>> x = 'I♥🐍' >>> len(x) 3 >>> x.encode() b'I\xe2\x99\xa5\xf0\x9f\x90\x8d' >>> len(x.encode()) 8 >>> x[2] '🐍' >>> x[2].encode() b'\xf0\x9f\x90\x8d' >>> len(x[2].encode()) 4So it turns out, that the three-character string 'I♥🐍' is actually eight bytes, with the snake emoji being 4 bytes long. But, in the encoded version of it, we can access each individual byte. And because it's a byte, its "value" will always be between 0 and 255:

>>> x[2] '🐍' >>> b = x[2].encode() >>> b b'\xf0\x9f\x90\x8d' # 4 bytes >>> b[:1] b'\xf0' >>> b[1:2] b'\x9f' >>> b[2:3] b'\x90' >>> b[3:4] b'\x8d' >>> b[0] # indexing a bytes object gives an integer 240 >>> b[3] 141

So let's take a look at some byte/bit manipulation examples:

def alternate_case(string):

"""Turns a string into alternating uppercase and lowercase characters."""

array = bytearray(string.encode())

for index, byte in enumerate(array):

if not ((65 <= byte <= 90) or (97 <= byte <= 126)):

continue

if index % 2 == 0:

array[index] = byte | 32

else:

array[index] = byte & ~32

return array.decode()

>>> alternate_case('Hello WORLD?')

'hElLo wOrLd?'This is not a good example, and I'm not going to bother explaining it, but it works, and it is much more efficient than creating a new bytes object for every character change.

Meanwhile, a memoryview takes this idea a step further: It's pretty much just like a bytearray, but it can refer to an object or a slice by reference, instead of creating a new copy for itself. It allows you to pass references to sections of bytes in memory around, and edit it in-place:

>>> array = bytearray(range(256))

>>> array

bytearray(b'\x00\x01\x02\x03\x04\x05\x06\x07\x08...

>>> len(array)

256

>>> array_slice = array[65:91] # Bytes 65 to 90 are uppercase english characters

>>> array_slice

bytearray(b'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ')

>>> view = memoryview(array)[65:91] # Does the same thing,

>>> view

<memory at 0x7f438cefe040> # but doesn't generate a new new bytearray by default

>>> bytearray(view)

bytearray(b'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ') # It can still be converted, though.

>>> view[0] # 'A'

65

>>> view[0] += 32 # Turns it lowercase

>>> bytearray(view)

bytearray(b'aBCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ') # 'A' is now lowercase.

>>> bytearray(view[10:15])

bytearray(b'KLMNO')

>>> view[10:15] = bytearray(view[10:15]).lower()

>>> bytearray(view)

bytearray(b'aBCDEFGHIJklmnoPQRSTUVWXYZ') # Modified 'KLMNO' in-place.bin, hex, oct, ord, chr and ascii: Basic conversions

The bin, hex and oct triplet is used to convert between bases in Python. You give them a number, and they will spit out how you can write that number in that base in your code:

>>> bin(42)

'0b101010'